Evolutionary Alarm Sounds within Languages

First Chapter Sample From:

Evolutionary Alarm Sounds within Languages

Christopher Richard Oszywa

Copyright © Chris Richard Oszywa 2003

This book is copyright apart from any fair dealings for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. The right of Chris Richard Oszywa to be identified as the moral rights author has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright Amendment (Moral Rights) Act 2000 (Commonwealth). Seaview Press

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Oszywa, Chris, 1968- . Evolutionary alarm sounds within languages.

ISBN 1 74008 269 9. 1. Language and languages - Economic aspects.

This book is dedicated to my two sons Otto and Alexander

First Edition: Evolutionary Alarm Sounds within Languages ISBN 1 74008 269 9. 1.

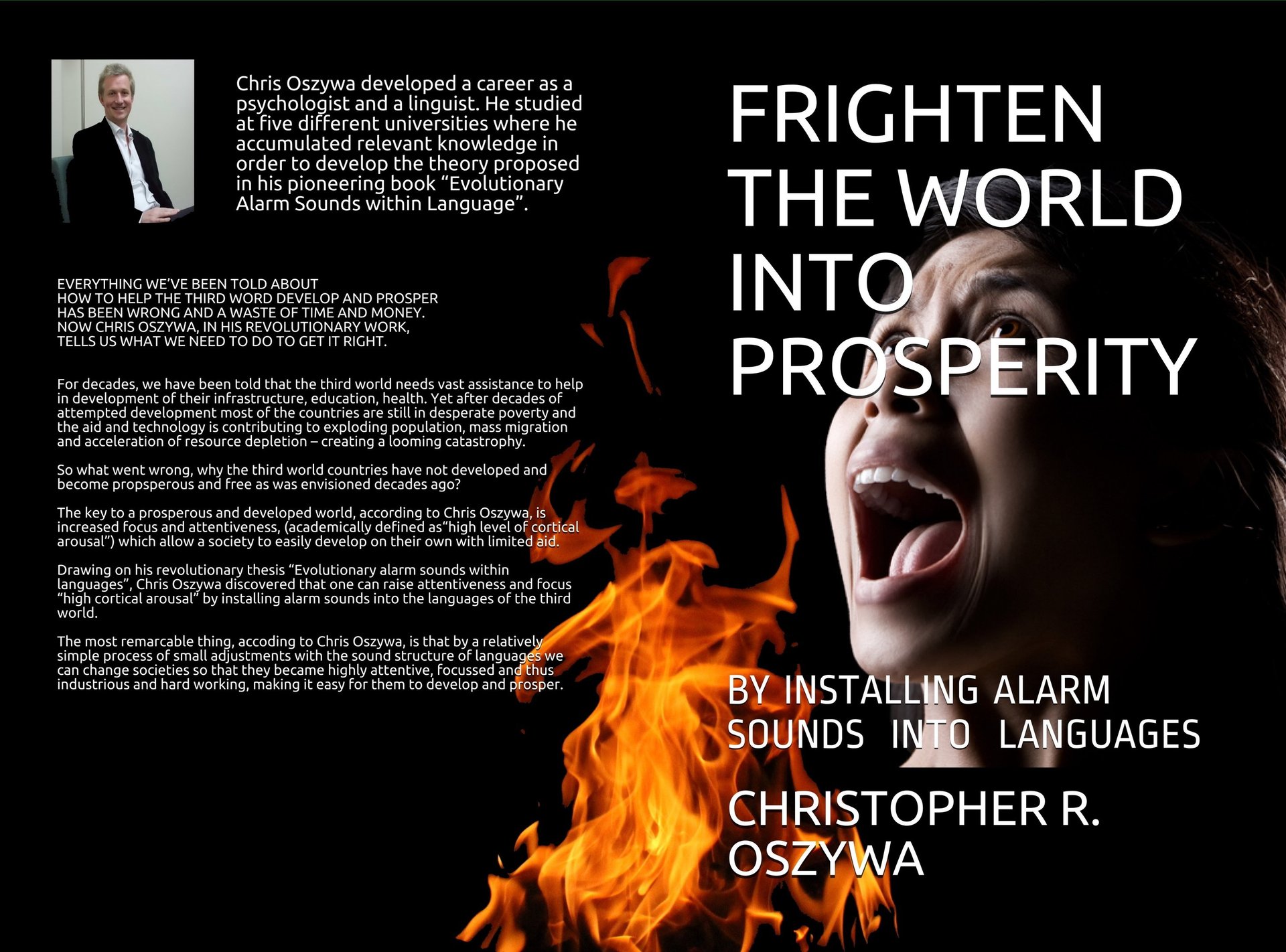

Second Edition: Frighten the World into Prosperity: By Installing Alarm Sound into Languages ISBN-13: 978-1700909930, ISBN-10: 1700909932

Third Edition (Smashword): Motivate Poor Countries to Develop: By Installing Alarm Sounds into Languages

Table of Contents

Preface

Chapter 1: Understanding Alarm Sounds within Languages and their Impact on the Economic Development of the World

Chapter 2: Languages with high concentration of alarm components

Chapter 3: Languages without significant amounts of alarm components

Chapter 4: Alarm Languages and Ancient Civilizations

Chapter 5: Understanding the Impact of Alarm Languages on Psychology and Behavior

Chapter 6: Putting It All Together — Emerging Theory of Economic Development

Bibliography

Appendix

About Author

Preface

You are about to be challenged by a fascinating concept that has been overlooked by philosophers and scientists for centuries. This book challenges the prevailing assumptions regarding the reasons behind historical developments. Consider the following questions: “Would Poles be as industrious as Germans if they spoke German as their primary language?”, or “Would India, Brazil or Ethiopia undergo economic development if they spoke Chinese Mandarin?”, or “Would ancient Rome still exist if the Romans retained their language as it was under the rule of Octavius Augustus?”. The disciplines of science, economics, psychology and philosophy have not yet succeeded in providing a testable and applicable theory which addresses questions such as these.

The differences in the distribution of wealth in the world have often been described in terms of the differences between the rich North and the poor South. However, the theory presented in this book argues that it may be more appropriate to conceptualize the differences in the distribution of wealth between the various countries in terms of the linguistic differences between them. For instance, the economically wealthy societies are also the ones which communicate using Germanic languages (including English, German, Dutch, Swedish and Norwegian) and Asiatic tonal languages (such as Mandarin, Cantonese, Japanese and Korean), while societies characterized by the poorest economic development are ones which, for instance, communicate using Arabic, Hindu or Portuguese languages.

This book presents a theory which outlines the missing link to our understanding of the many inconsistencies which abound in today’s world. The theory may assist us in understanding why some societies (for example, the Chinese) are able to thrive economically while others continue to live in extreme poverty (for example, African or Indian societies).

The basic assumption underlining the concept presented in this book is that, for a given society to develop economically, its members must demonstrate a heightened state of alertness, as if they were unconsciously and constantly affected by fear. Pavlov (1927) defines this state as “heightened excitability of the cortex cells” and Eysenck (1967) defines it as a “high habitual level of cortical arousal”. The above three definitions will be used interchangeably throughout this book as they refer to the same concept.

ln easily observable terms, a heightened state of alertness is characterized (among other things) by behaviours that reflect introverted and anxious tendencies, such as those seen in a high proportion of individuals from Chinese, Japanese or Swedish societies. Pavlov (1927) describes individuals with a heightened state of alertness as having a meek nature, while Eysenck (1967) describes them as being introverted.

To achieve this heightened state of alertness, human beings must be stimulated through a primitive evolutionary communication system which evolved to give human beings and other members of the animal kingdom the ability to automatically perceive threats in their external environments. As human beings and animals perceive such threats, they instantaneously produce alarm signals to announce danger to other group members. In his book “Brain Reflexes”, Ivan Sechenov (1866) describes this type of reaction as an evolutionary brainstem reflex. This tendency is universally similar among the various animals comprising the evolutionary scale.

The crux of this theory, the facets of which will be explored in more detail in subsequent chapters, is that one can alter a current language or create a new language which contains a high concentration of evolutionary alarm sounds. If such a language were to be constructed, it would automatically increase the alertness of the individuals who use it as their means of communication, creating a psychological environment favourable for the creation of economic progress (a favourable environment is conceptualized as behaviours associated with higher cortical arousal, as will be explained in detail throughout the book).

In the past, the languages of many highly civilized societies (such as the ancient Greek and Roman civilizations) contained alarm sounds within their structures. Because of the phenomenon of “language change”, the alarm qualities within those languages were gradually replaced with other sounds, and as a result, these societies exhibited corresponding downfalls.

In modern times, the most industrialized societies of the world speak languages that contain many evolutionary alarm sounds within their syllables (e.g., the German language). Conversely, the languages of societies which struggle economically do not contain many evolutionary alarm sounds (e.g., the Hindu language).

To better illustrate this, let us consider an analogy. Just as good soil is a necessary precondition for the growth of plants, I am suggesting that adequately high alertness (high cortical arousal) within individuals who comprise a society is a necessary precondition for the development of factors which enhance economic growth within that society (high cortical arousal is necessary for people to pay attention to details and to be trained). Increased alertness in a society can be brought about by having the population communicate using a language which contains many evolutionary-based alarm signals (alarm sounds are brain stem reflexes that automatically trigger an arousal reaction in the nervous system and throughout the body. Continuous exposure to these reflex reactions in response to alarm sounds present in a language increases the habitual cortical arousal level).

This book begins with an exploration of alarm sounds, describing their usefulness in a natural ecological setting and the ways in which they exist within syllables of languages.

The second and third chapters evaluate the major languages of the world in terms of the concentration of alarm sounds within their syllables. I particularly draw attention to the high correlation between the concentration of alarm sounds within syllables of languages and the economic development of countries which utilize such languages.

The fourth chapter demonstrates that languages used by many highly economically and structurally developed ancient civilizations, such as the ancient Greek and Roman civilizations, contained high concentrations of alarm sounds within their syllables, as compared to less developed civilizations.

Chapter five investigates the impact of the concentration of alarm sounds within languages on the psychology and behaviour of individuals who utilize such languages.

Finally, chapter six describes the impact that alarm sounds within languages have on the economic development of countries, suggesting that adequate levels of alertness (as conceptualized using Wundt’s “inverted U” relationship between arousal and performance) are necessary for economic growth. It suggests that too high cortical arousal can be detrimental to society. Chapter six also provides a simple blueprint of application so that the third world can quickly adopt the theory presented in this book and become economically developed and prosperous.

Chapter 1

Understanding Alarm Sounds within Languages and their Impact on the Economic Development of the World

1.1 Background Information

For thousands of years, historians have pondered the reasons behind the rise and fall of civilizations. It is commonly believed that civilizations advance if they possess a combination of factors which allow them to develop and prosper economically. Among these factors are a well-developed education system, a wealth of natural resources (e.g., minerals and fertile soil), military power, good leadership, a lack of corruption and decadence, a diligent work ethic and extensively developed trade networks.

Just as the presence of any one or more of the above factors has been used to explain economic advancement and prosperity in certain civilizations, economic hardships and declines have been attributed to the lack of any one or more of the above components. For instance, the decline of ancient Rome has been traditionally attributed to corruption, a loss of trade and opponent military strength.

Figure 1. Imperator Augustus Octavius (63 B.C.-A.D. 14) is credited with bringing Rome to its golden age. Latin was an alarm language during the time of Augustus, and it was this alarm quality that gave the drive and focus to the Roman people to create their remarkable civilization, which was the blueprint for our modern world.

In addition to asking why ancient civilizations rose and fell, many modern thinkers are puzzled by a comparable question, that is, why some societies have been able to become industrialized while many others have remained industrially undeveloped. When one looks at the economic performance of countries around the globe, it becomes apparent that there exists an enormous discrepancy in the rate of economic development and competitiveness in the various regions.

To date, the wealthiest and most industrialized regions of the world are the Western countries (Western Europe, North America and Australia) and the Asia Pacific countries (Japan, Korea, China, Taiwan, Singapore and Malaysia).

On the other hand, most of the regions that comprise South America, Africa, the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent are unable to develop their economies to the extent seen in Western countries and Asia Pacific countries.

Over the years, various national governments and institutions, such as the United Nations, have tried to advance the economic progress of some of the most underdeveloped areas of the world by attempting to create within them an environment which is benevolent to their industrial progress. They hoped to do this by introducing these societies to some of the factors which are generally believed to be responsible for the economic growth and decline of societies.

For example, some of the representatives of the United Nations’ institutions believed that education was the key factor influencing the economic development of various economically underdeveloped regions of the world. Hence, over the years, using enormous financial resources, the United Nations initiated various education programs (for example, in 1961 McClelland began conducting training courses aimed at reinforcing the achievement motive; the United Nations Industrial Development Organization still delivered such courses in the 1980s). Unfortunately, these educational programs did not live up to their expectations, doing very little to advance the economies of these economically underdeveloped countries.

To date, many authorities from the disciplines of psychology, sociology and economics continue to search for ways to advance the economic development of underdeveloped regions in the world. Some of the explanations which have been proposed to understand the failure of Third—World countries to develop their economies are similar to the traditional explanations that have been put forward to understand the rise and fall of many ancient civilizations.

Among the many authors who have put forward theories to explain why certain civilizations rose and fell are Toynbee (1947) and McClelland (1961). Toynbee suggested that the economic growth of a society is dependent on the presence of a challenge in its environment; this challenge may be either internal or external. On the other hand, McClelland believed that the economic progress of a society is proportional to the strength of its achievement motive; achievement motive motivates a population to action.

Figure 2. Education has been a favored approach for attempting to create economic progress. If a society speaks an alarm language like Chinese or Vietnamese, then education will greatly accelerate economic development.

Unfortunately, among the many theories that have been proposed to explain why certain civilizations fall, not a single one convincingly explains the fact that some societies and not others are able to develop the above factors. Similarly, not one offers lasting, applicable solutions to the economic hardships and struggles of Third-World countries. It is true that each of the factors mentioned above has the potential to contribute to the economic growth of a society. However, I believe that there exists an underlying mechanism which affects the ability of a society to develop the above factors.

This mechanism is dependent on individuals in the society having “heightened excitability of the cortex”, as described by Pavlov (1928). Heightened cortical arousal has cascading effects on behaviour; these behavioural effects are essential or desirable for a society to develop economically. The effects on behaviour include an increase in conditional reflexes, which enhances and facilitates training. Further, people with heightened cortical arousal worry more about every aspect of society and the economy. It is important to note that people cannot be educated to have high cortical arousal, that is why people cannot be taught to be more easily trained or to more readily follow rules and instructions (Eysenck, 1967).

This phenomenon explains why many poor societies around the world, whose cortical arousal levels are low, are not able to benefit from programs that were designed to help them to improve their economies. On the other hand, communities in undeveloped societies where there is high cortical arousal tend to absorb and benefit from these programs, as has been the case with China and is currently occurring in Vietnam.

1.2 A New Theory: A Practical Approach to the Acceleration of Economic Growth in the Third World

The assumption that underlies this theory is that, for a given society to develop economically, its members must demonstrate a heightened state of alertness (or higher cortical arousal). Specifically, I believe that, to achieve this heightened state of cortical arousal or alertness, human beings must be stimulated via a primitive, evolutionary communication system.

This primitive evolutionary communication system has especially evolved to enable human beings and other members of the animal kingdom to automatically perceive threats in their external environments. When human beings and animals perceive a threat in their environment, they instantaneously produce alarm signals (alarm sounds/fear sounds are a brain core reflex; they are hard-wired into the brain). This tendency is universal among the various animals on the evolutionary scale.

Figure 3. Man has undeniable connections and similarities to other animals on the evolutionary scale. We can utilize this evolutionary mechanism to increase “cortical arousal” of the third world countries so that they have the focus and attentiveness to quickly develop economically.

The crux of the current theory, the specific facets of which will be explored in more detail in the coming chapters, is that one can actually create a language, or alter a present language, so that it will contain within it many evolutionary alarm sounds. If such a language were to be constructed, it would automatically increase the levels of alertness in individuals who use this language as their means of communication. This, in turn, would create a psychological environment for individuals which is advantageous for social economic progress.

In the past, evolutionary alarm sounds were contained in the languages of many highly civilized societies. As the alarm qualities within these languages were gradually replaced with other sounds, the societies experienced a corresponding economic downfall.

1.3 The Evolutionary Communication System

The role of evolution in the selection of behaviours that maximize the chance of survival of human beings and other animals has long been investigated, see Darwin (1965). The behaviours and information-processing systems that aid the survival of human beings and other animals are controlled by brain structures which are believed to have evolved at the early point, perhaps as far back as 500 million year, including the mammalian limbic system and the archaic reptilian core.

Specifically, the mammalian limbic system and the archaic reptilian core control the automatic physiological reflexes of human beings and other animals; these automatic physiological reflexes directly support the life of the organism, for example, breathing and heartbeat. Additionally, the mammalian limbic system and the archaic reptilian core control some of the psychological automatic reflexes, one of which is our innate ability to recognise and produce alarm sounds (this system is probably one of the earliest systems already present during the dinosaur era).

When feeling afraid or when perceiving a life-threatening situation, animals and human beings produce signals that communicate their fear and distress to other animals, both within and outside their own species. In 1960, Collias pointed out that one of the most automatic responses that animals make in the presence of an enemy is to announce the enemy. In this way, possible danger in the environment can be communicated to animals in the vicinity of the dangerous situation or stimuli.

Auditory signals are of central importance here. For example, birds and mammals heed the warning sounds produced by other animal species. An example of this is the tendency of seals and sea lions to flee in response to the warning sounds produced by gulls and cormorants, even though gulls and cormorants tend to be much more alert to the approach of danger than are seals and sea lions (Bartholomew, 1952).

Figure 4. A call of a frightened bird is automatically perceived by other species of animals as an alarm call. Alarm sounds have universal similarities across species. It is this type of alarm sounds that if present in language motivate the society to become focused and attentive, making it easier to develop economically.

Many more examples of the inter-specificity of alarm and distress signals among birds are provided by Busnel (1963). The common characteristics of distress sounds of birds include loudness, harshness, high pitch, and in most instances, prolonged quality. Loud, high-pitched and prolonged sounds are also characteristic of the alarm calls of many other animals, such as human infants, insects, fish and anurans.

Evolution intended alarm sounds to be loud, high-pitched and prolonged. Sounds that share these qualities are universally perceived by the majority of animal species as distress signals. Hall (1947) demonstrated this very well by showing that the fear-inducing effect of sounds which are loud, harsh, high-pitched and prolonged elicit extreme reactions in some animals. For instance, at the ringing of an alarm clock, several abnormally sensitive strains of mice were found to race madly about, go into convulsions and die.

In 1953, Collias and Joos investigated the loud and harsh alarm calls of flying hawks. These alarm calls instantly cause flying hawk chicks to run short distances and then freeze into silent immobility. Even taped playbacks of these calls have this effect on flying hawk chicks.

Rosenhouse (1977) brought to light the fact that human infants also give out alarm sounds which differ depending on whether the infant is hungry, ill or in pain. This suggests that human infants have an inborn, evolutionary-based system that processes and vocalizes alarm sounds (such a system would be described by Ivan Sechenov (1866) as a brain reflex, or later, as a brain stem reflex).

Figure 5. The distressed cry of a baby is automatically perceived by the parents, other humans and pets as an alarm or distress call. Alarm sounds have universal similarities across species.

It is possible that the evolutionary component of the structure of alarm sounds originated from what is termed “the freezing phenomenon”. Alarm sounds produced by animals in response to a perception of threat are characterized by their un-malleable and fixed structures, appearing “frozen” and still (as if stuck and unable to change), just as the animals themselves appear motionless and still in response to perceived threats. Givens (1978) pointed out that the freezing phenomenon is common among mammals and even manifests itself in human infants by four weeks of age.

The words of Clynes (1989) are the perfect way to summarize this evolutionary level of information processing: “... nature has made the communication of emotions elegantly simple” (1989, p.7). By this, Clynes means that our ability to recognize emotions is genetically encoded, so that emotions are automatically responded to by our nervous system (and perhaps we could describe the recognition of all emotions as a brain reflex).

1.4 Understanding Alarm Sounds within Languages

All alarm calls show strong ecological similarities; they can be distinguished from non-alarm sounds by their long duration and regular structure.

Figure 6. A simplified voiceprint of a blackbird’s alarm call.

The horizontal axis of the voiceprint in Figure 5 depicts time and the vertical axis depicts pitch, which is measured in cycles per second or hertz. Note that the above voiceprint contains the characteristics of an alarm sound as it has a long duration, and the symmetrical structure of its dark bands indicates regularity. These dark bands are also present in human speech. The dark bands in a human voiceprint represent sounds that have the acoustic characteristics of vowels, as is illustrated in the voiceprint below (Figure 6), which depicts the diphthong [ei].

Figure 7. A voiceprint of the vowel [ei], as pronounced in the syllable ‘haid’.

When human beings speak and when animals vocalize, pulses of air are produced. It is within these pulses of air that alarm sounds are contained. In linguistic terminology, a pulse of air is referred to as a syllable.

For example, the word “today” contains two syllables, [to] and [day]. The second syllable in the word “today”, [day], embodies two vowels that are next to each other, [a] and [y]. When put together, the combined length of these two vowels is approximately 0.25 of a second, which is sufficiently long for this combination to constitute an alarm sound. For a sound to be considered an alarm sound, it needs to be around 0.15 to 0.18 of a second or longer in order to trigger a fear reflex in the brain stem.

1.5 Creating Alarm Sounds by Combining Vowel- Like Sounds

Sounds that have the acoustic qualities of vowels appear on voiceprints as dark bands. Acoustic vowel sounds are characterised by periodical lines, which appear as vertical lines on a voice print. These can be sub-divided into five categories: vowels, semivowels, diphthongs, nasals and approximates.

Vowels include the sounds: [i], [e], [a], [o] and [u]. Semivowels include the sounds [i] and [w]. Diphthongs include the sounds: [ei], [ai], [oi] and [au]. Nasals include the sounds: [m], [n] and [ng]. Finally, approximants include the sounds [l] and the English [r]. Note that the ‘r’ and ‘w’ sounds have acoustic vowel qualities in English, but not necessarily in other languages, for example, Dutch. For further detail about the various pronunciations of [r] refer to Catford (1990).

When isolated, some vowels are more than 0.15 to 1.8 of a second in duration; hence, they meet the criteria for being considered an alarm sound. For instance, the long vowel [aa] in the Dutch word “maan” has a duration of about 0.2 of a second (note that vowels shorter than 0.15 of a second, when produced at a higher pitch or intensity, could also be considered alarm sounds as they would also most likely trigger a reflex reaction in the brain stem).

Further, most combinations of diphthongs and vowels result in durations of more than 0.18 of a second. For example, the duration of “ow” pronounced [au] in the word how is approximately 0.3 of a second. For further information on this, refer to Deighton and Koopman’s (1974) “Aspects of English Vowels”, in which the authors demonstrate that [au] is approximately 0.288 to 0.3 seconds in length when produced in an isolated word.

Combinations of two or more sounds that have the acoustic of vowels also result in durations longer than 0.18 of a second. An example of this is the word “on”, where the vowel [o] is followed by [n], or the word “call”, where the vowel [a] is followed by the approximant [l]. Another example of a syllable with alarm qualities is the word “why”, which is a single syllabic word that has a very long vowel quality of approximately 0.45 of a second.